Part 1 - The big idea

The prelude

So I decided to build my own C2 framework. Because clearly, what the community needs is yet another command control framework and picking from the long list of existing well-written frameworks would be far too easy. Mild sarcasm aside, here are just some of the reasons which drove me to begin this project:

-

Learning Style: I’ve gained solid knowledge of C2 frameworks and how they function under the hood. Building one from scratch was the next step in mastering their design and inner workings. (I have always been a hands on learner rather than a bookworm.)

-

Curiosity: Fixing bugs and customising frameworks to my needs presented the question “how hard can it be?” more than a few times.

-

Real Interest: Believe it or not I actually enjoy this subject matter meaning the process of developing my own C2 was super fun… for the most part.

Right, so now that all the mundane context is out of the way, let’s get into what this series is actually about.

I decided to document the process of building my own C2 framework, step by step. At the time of writing, I’ve got no clue how many parts this will end up being. The original idea was selfish, honestly, a way for me to look back and see the full journey, wins and failures included.

But then I figured… maybe someone else out there is on the fence about starting a big personal project. Maybe seeing this chaotic series unfold in public will give them the push to go build the next great offensive/defensive tool, or at least start tinkering. So here we are. This series is basically a dev diary. It won’t be perfect. I’ll make wrong choices, break things, probably change my mind a few times, but that’s kind of the point.

Down to business

Understanding the core principles behind how a C2 framework operates was the first concrete step in shaping the goals for my own project. While I was already well-versed in how most C2s function, having used a wide range of them across both commercial and open-source offerings, I still felt it was worth taking a fresh look through a practical lens. I spun up several frameworks I’ve used in past engagements, paying close attention to the operator workflows, flexibility, and pain points that tend to crop up mid-op. Some tools nailed the tasking flow and session handling. Others buried useful functionality behind unnecessary complexity or awkward UIs that got in the way of speed and control.

The aim here wasn’t to reinvent the wheel, or clone someone else’s, but to take the lessons learned from real-world use and build something that matched how I prefer to operate: clean, fast, modular, and tailored for team use without bloated overhead. This research and my existing knowledge led me to break the project down into 4 smaller sub projects, see below the high level breakdown:

-

Team Server: Often called the brain of the operation, the team server is arguably the most critical component of the framework. It manages the entire ecosystem, handling operator sessions, beacon (agent) sessions, task distribution, and result tracking. Additionally, it maintains a persistent record of all activity to support post-operation analysis, auditing, and debugging.

-

Operator UI: The operator UI provides red teamers with an efficient, practical interface to interact with the team server. Whether it’s listing active beacons, assigning tasks, or retrieving output, this interface serves as the primary gateway into the framework’s core functionality.

-

Agent (Beacon): The agent, commonly known as the beacon, resides on the target system. Its role is straightforward but essential: maintain regular communication with the team server, receive and execute assigned tasks, and send back the results.

-

Communication Medium: This is the channel through which the agent and team server exchange data—enabling task delivery, execution, and result reporting. Common protocols include HTTP(S) and DNS, especially for external communications, chosen based on stealth, reliability, and network environment.

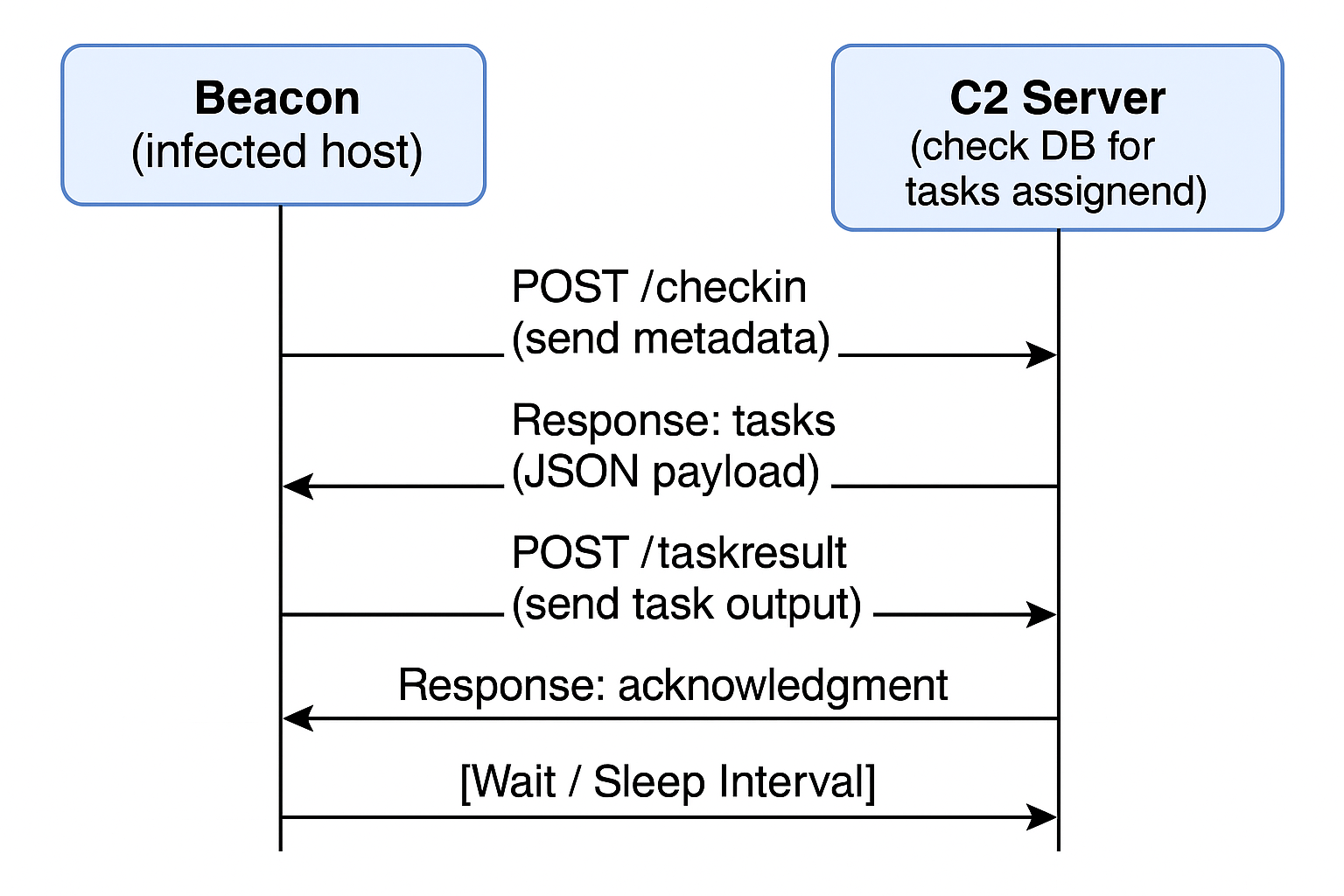

Below is a very high-level overview of how each component interacts over the course of around 60 seconds. Caveat! This is a crude, back-of-a-napkin-style diagram — it’s not meant to show every detail, but it gives a rough idea of how the system should operates at a glance.

What started as a large, daunting project eventually took shape as four manageable sub-projects, each with a clear role in the bigger picture. Once I broke it down, it became obvious that I wouldn’t be able to build each component in isolation, I’d need to jump between them and develop in unison to keep everything aligned. With that in mind, and the phrase “If you don’t know where to start, just start” echoing in my head, I decided to begin with the low-level design and requirements of the team server itself.

The Team server

Starting with the team server, the first big decision I need to make is choosing the language and runtime. I have to think ahead to the finished product — switching languages halfway through isn’t something I want to deal with. On top of that, I need to factor in how the components will interact and how the overall architecture can scale. Now, full transparency: I’m not a developer by trade. My background is in offensive security, and everything I know about writing code is self-taught. So whatever language I pick, I know I’ll be learning as I go. That said, I’ve already built tools like GW-Ransomware and GW-Exfiltrator in C# and C++, so I decide to go with what I’m most comfortable with — C# — in the hopes of keeping the learning curve manageable.

To get a better handle on the architecture, I start digging into the .NET ecosystem — .NET Core, .NET Framework, .NET (depending on who you ask, they’re either all the same or completely different). Down the rabbit hole I go. After a bit of research (and some pain), I come out the other side having landed on .NET (modern and cross-platform), mainly because of its long-term support and solid cross-compatibility.

Next step: Visual Studio. Time to pick a project type. You already know what’s coming — yep, straight back down the rabbit hole. I won’t bore you with the full comparison list, but in the end I stick with a Console App. I’ve used it before, it keeps things simple, and while I briefly consider ASP.NET, I decide against it to keep things as lean and familiar as possible for now.

TL;DR – Team Server Setup Decisions:

- Language: C#

- Runtime: .NET (modern version, not .NET Framework or .NET Core)

- Project Type: Console App (for simplicity and familiarity)

The Operator UI

The next logical step is figuring out how an operator will interact with the team server. I need a clear flow for how commands are issued, authenticated, processed, and how responses are returned. Right from the start, I know I don’t want to rely on a traditional GUI — this is going to be a CLI-driven setup, built for flexibility and speed.

I begin mapping out the command flow: an operator connects over TCP, authenticates, enters a tasking session with a specific beacon, and starts issuing commands. Each of those commands needs to be tracked, stored, and routed to the correct beacon — and then the results have to make their way back through the same path, all tied to the right session. There are a lot of moving parts to think about: session management, beacon routing, command history, error handling — all while keeping everything modular and maintainable. This stage is really setting the foundation for how operators will actually use the framework during an engagement.

I find myself jumping between ideas and testing different approaches. I trial a bunch of existing C2 frameworks, not to clone them, but to cherry-pick the best bits that align with what I’m building. And for the same reasons I chose C# and .NET for the team server — simplicity, compatibility, and familiarity — I decide to use the same setup for the operator UI. Keeping both sides consistent should help cut down complexity and reduce the overhead of switching contexts as I build.

TL;DR – Operator UI Setup Decisions:

- Language: C#

- Runtime: .NET (modern version, not .NET Framework or .NET Core)

- Project Type: Console App (for simplicity and familiarity)

The Agent (Beacon)

Now onto the agent — or, more accurately, the planning for it.

This is one part of the project I deliberately hold off on making any hard decisions about early on. Even though I’ve got solid experience in malware development, I know the agent is going to be the most complex and sensitive part of the entire framework. It’s where opsec, evasion, communication, and execution all collide — and cutting corners here just isn’t an option.

I also know that building the agent will likely push me out of my comfort zone more than any other part. While I’ve mainly worked in C# and C++, I’m expecting to dip into languages and tooling I’ve had far less hands-on experience with — whether that’s Go, Rust, or even assembly in certain contexts. So rather than rushing in, I make the call to park the agent for now. It’s going to need a dedicated planning phase, and trying to juggle that alongside the team server and operator development would just create unnecessary overhead. Once the backend is stable and the operator UI is nailed down, I’ll shift gears and give the agent the full attention it demands.

In the meantime, to keep development moving, I’ll simulate agent traffic using some crude scripts — just enough to test the communication flow between the team server and the operator UI. It’s not pretty, but it’ll help validate the backend logic and keep progress unblocked while the real agent takes shape later.

The Communication

With the broad components sketched out, the next thing I need to wrap my head around is how everything will actually communicate. Nothing’s been built yet — this is still very much in the planning phase, but I want to get a clear picture early so I don’t run into integration headaches later. Starting with the operator-to-team server communication: I’m planning to keep this part simple and direct — just a TCP socket connection. The operator will connect, authenticate, and interact with specific beacons through tasking sessions. Straightforward, clean, and something I can easily build on.

Then comes the agent comms, which is obviously where a lot of the real fun (and complexity) lives. For the initial version, I’m planning to support:

- HTTP/HTTPS, using standard GET/POST requests for beacon check-ins and tasking

- A basic DNS channel as an alternative — likely abusing TXT or A records to start with

This setup gives me flexibility without being overwhelming. I’ve seen plenty of variations across different frameworks, so I’m borrowing the best ideas and working toward a model that makes sense for what I want to build. For internal communications, I’m leaning towards using SMB. It’s a familiar option for lateral comms and peer-to-peer messaging between beacons inside a network, and I’ve used it in other tooling before.

I’m purposely not trying to build everything at once — the plan is to start small, validate it works, and then evolve it. Features like encryption, jitter, alternate protocols, and traffic shaping will come later once the foundations are in place.

TL;DR:

Communication is still in the planning stage. Operator connects to the team server over simple TCP. Agents will use HTTP/HTTPS (GET/POST) and DNS for external comms, with SMB planned for internal beacon traffic. Starting small and building up features over time — nothing’s set in stone yet.

What now?

At this point, I’ve got a solid foundation laid out. The big design choices are made, the moving parts are roughly mapped, and I’ve got a good idea of how everything should fit together — in theory.

Now comes the part where I actually have to build the thing. No more diagrams, no more “just planning” excuses — it’s time to open that blank .cs file and start making it real.

I’ve scoped enough to avoid biting off more than I can chew (hopefully), but let’s be honest — this is where things get messy, and I fully expect to be debugging some strange behaviour at 2am wondering why I ever thought this was a good idea.

Let’s build a C2 framework. What could possibly go wrong?

Red Teaming GWC2 DevSeries